I saw the apomorphine treatment really work. Eight days later I left the nursing home eating and sleeping normally. I remained completely off junk for two full years – a twelve year record. I did relapse for some months as a result of pain and illness. Another apomorphine cure has kept me off junk through this writing.

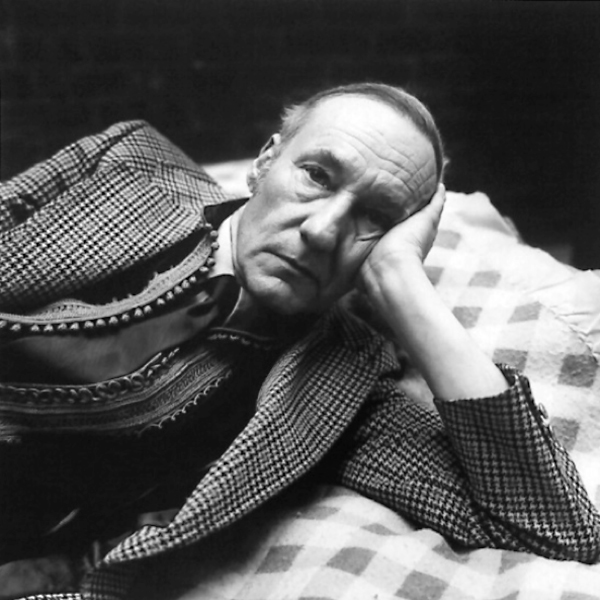

Introduction to ‘The Naked Lunch’ by William Burroughs

William Burroughs: writer, cultural icon, and ‘master addict’ claimed he was never completely cured of the craving for morphine until he took Dent’s apomorphine treatment in 1956. His life-long advocacy on the merits of apomorphine as an anti-addiction medication helped maintain knowledge of its existence long after it fell out of favour within the medical establishment.

Burroughs was born in the United States to a wealthy and well connected Missouri family. He began writing in his teenage years and excelled academically at school. He read English at Harvard and with the idea he might become a doctor took a conversion course in medical studies at the University of Vienna. With the rise of fascism in Europe he returned to the states in 1937 and completed a post graduate in Anthropology at Columbia University.

Burroughs identified himself as a homosexual from an early age. He saw himself as an ‘outsider’ at odds with the expectations of his background: to settle down and pursue a reputable career. However, Burroughs’s ambition was to be a published writer. A private income gave him the freedom to travel and immerse himself in experiences which he would draw on in his writing. In the years leading up to America’s involvement in World War 2 he sought out low paid employment, mix with rule breakers and exiles and involved himself in situations that strayed beyond the expectations of his upbringing.

By 1940, aged 34, Burroughs was addicted to opiates. Looking back at his long life he stated that becoming a junky was one of the best things he did. Drugs enabled him to experience the world differently and to write. Privately he needed drugs and alcohol to alleviate anxiousness and fear of failure.

Burroughs took many cures throughout his long life and until he became financially independent from his writing was reliant on family money to support and manage his addictions. Following the publication of his seminal work The Naked Lunch (1959) his addiction was monitored by a circle of close friends.

Burroughs break through as a recognised writer came following the U.S. publication of Naked Lunch in 1962. It launched his career and reputation as a writer in North America and Northern Europe. Burroughs credited his discovery of apomorphine in 1956 as representing the ‘turning point between life and death. I would never have been cured without it. Naked Lunch would never have been written.’

Burroughs spent much of the 1950s in Tangiers following the accidental death of his wife for which he was culpable. Free from domestic responsibilities (his son was looked after by his parents), he combined a hedonistic lifestyle with bursts of writing semi-autobiographical fiction.

In 1956 seriously ill from addiction to Eukodol, a legalised form of morphine, Burroughs was urged by his father to seek treatment in London. Unable to look after himself and hardly recognisable to those that knew him Burroughs ‘pulled himself together’ and travelled to London where he was recommended to Dr John Yerbury Dent who had a ‘good rate of success with addicts.’

Burroughs was sceptical of the motivations of cure doctors but Dent was different. He appeared honest to Burroughs and his book ‘Anxiety and Its Treatment’ struck a chord. Dent convinced Burroughs of the efficacy of apomophine as a metabolic regulator and he undertook the treatment in April. Writing to his long term friend and collaborator Allen Ginsberg he described the experience as ‘difficult’ and ‘awful’ but then added … ‘I had a real croaker (Dent) interested in Yage, Mayan Archaeology, every conceivable subject’. As the treatment progressed Burroughs came to like Dent. He found him reassuring and prepared to talk through the night when he couldn’t sleep. Following the cure Dent entertained Burroughs at his home and encouraged him to resume writing, commissioning an article for The Journal for The Study of Addiction which he edited.

Burroughs considered Dent’s approach a success. He wrote to Ginsberg: ‘Junk … Speaking of which I never feel the slightest temptation’, and ‘Since the cure I been sexy as an eighteen year old and healthy as a rat.’ He also reported that Dent had provided him with ‘a stock pile of apomorphine’ in case of relapse. Four months after receiving the treatment Burroughs was back in Tangier, maintaining a healthy lifestyle which included satisfactory sex and writing new material that would appear in ‘Naked Lunch’.

In Burroughs’s article Letter from A Master Addict to Dangerous Drugs, published by Dent in January 1957, he summarises the narcotic effects of different drugs and cures he had received. On apomorphine he writes:

Apomorphine is certainly the best method of treating withdrawal that I have experienced. It does not completely eliminate the withdrawal symptoms, but reduces them to an endurable level. The acture symptoms such as stomach and leg cramps, convulsive or maniac states are completely controlled. In fact apomorphine treatment involves less discomfort than a reduction cure. I feel that I was never completely cured of the craving for morphine until I took apomorphine treatment. Perhaps the ‘psychological’ craving for morphine that persists after a cure is not psychological at all but metabolic. More potent variations of the apomorphine formula might prove qualitatively more effective in treating all forms of addiction.

Burroughs sought Dent’s treatment for a second time in 1957 having become addicted to heroin in Paris. Again apomorphine helped Burroughs to overcome his craving for junk.

In the years leading up to Dent’s death in 1962 Burroughs’s friendship with the addiction specialist deepened. They corresponded and met on several occasions and he learnt of Dent’s struggle to get apomorphine recognised as a non-emetic treatment for addiction in Great Britain and the United States. Throughout the 1960s until the treatment’s decline in the 1970s Burroughs widely promoted the treatment. He included Letter from A Master Addict… in the appendices of the 1962 and 1967 editions of Naked Lunch and published a series of interviews titled ‘Academy 23’ outlining his knowledge on apomorphine, his experience of receiving it and his hypothesis on why it wasn’t widely available.

Pharmaceutical researchers are told what research to pursue by vested interest, which gives orders to the American Narcotics Department. Billions for variations on the Benzedrine formula, for tranquilizers of dubious value, not ten cents for a drug that has unlimited potentials not only in treating addiction but in handling the whole problem of anxiety.

Burroughs can be credited with prompting the treatment’s revival in the 1970s. Some addicts convinced doctors to investigate the potential of apomorphine to treat opiate and benzedrine addiction. Doctors Beil in Hamburg, Lock Halvorsen and Martensen Larsen in Copenhagen and Schlatter in Ottowa familiarised themselves with Dent’s methods and conducted studies on addicts using oral preparations and non-aversive dosages of apomorphine. Their published papers confirmed that apomorphine stopped craving, revived potency, reduced anxiety and improved cognition. They also reported that the drug was difficult and time consuming to administer. For it to be effective, it was suggested that each patient required their own dose and therapeutic treatment plan.

When the treatment became unavailable in the UK from 1968 Burroughs directed addicts to one of Dent’s nurses, Smitty, who unofficially obtained and administered apomorphine using Dent’s method. Keith Richards records in his autobiography Life being recommended apomorphine by Burroughs. The experience, not as Dent would have given it, was a botch job and ‘didn’t work’.

After having lived outside the United States for 24 years Burroughs returned in 1974. He lectured and continued to write inspiring a new generation of artists, musicians and writers. The publication of Naked Lunch had given him fame and financial security. In 1981 he settled in St Lawrence Kansas and was based there until his death in 1997 aged 83.

Throughout his adult life Burroughs never achieved total abstinence from drugs or alcohol. On his return to the United States he relied on close friends to look after his health. He took many cures but the one that remained the most documented was apomorphine

Dent’s treatment may well have disappeared into obscurity had it not been for Burroughs’s continued endorsement of it and the referencing of his apomorphine experience by biographers and pundits. This alone has kept the knowledge of Dent’s treatment in circulation despite it disappearance from the field of addiction research and treatment services.

I suggest that research with variations of apomorphine and synthesis of it will open a new medical frontier extending far beyond the problem of addiction.

William Burroughs, Introduction, ‘The Naked Lunch’, 1957.

Image Credit

William Burroughs (I), 1975

Peter Hujar

©1987 The Peter Hujar Archive LLC;

Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Fraenkel