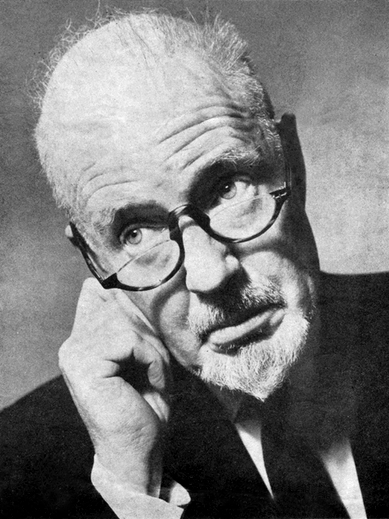

Patrick Riddell was born and brought up in Belfast, the son of a prosperous journalist. On leaving school he entered the Ulster civil service but his ambition was to be a successful writer. In 1931, aged 27, Riddell transferred to London to work for the Department of Overseas Trade. The move enabled him to pitch ideas for theatre and radio work and, with guidance from the producer Tyrone Power, his adaptation of ‘The Three Musketeers’ was broadcast by the BBC in 1932. This was followed by a dramatized serialisation of ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’. Its success guaranteed more radio drama commissions. Riddell also became a regular contributor to The Irish Daily Express.

Riddell started drinking at 22. By the time he moved to London he was a chronic alcoholic and in debt; despite a regular salary and fees from his freelance writing he was unable to control his spending. He drank to alleviate anxiety exacerbated by his punishing workload. His alcoholism affected his domestic life and by the start of the second world war Riddell’s wife Eileen left him to join her family in Belfast with their three young children. After an uneventful war, in which Riddell saw no action, he returned to London and resumed his civil service work and freelance writing. Reunited with Eileen his drinking remained a serious problem. In 1947 he was persuaded to seek help by a school friend, George Kinnaird, who was also an alcoholic. He recommended Dr John Dent’s apomorphine treatment, and Riddell agreed to try it. He was 43.

The apomorphine treatment worked. Riddell would credit it for helping him to remain abstinent from alcohol for the rest of his life. Following the cure he returned to Eileen and the children in Belfast and took up a new post in the Ministry of Commerce.

Riddell devoted much of his time and energy trying to help other alcoholics. In 1955 his book ‘I Was An Alcoholic’ was published. It describes Riddell’s descent into alcoholism and its effect on his professional and domestic life. It also includes a detailed account of Dent’s apomorphine treatment. Following the book’s publication he continued to draw attention to the treatment and recommended patients to Dent. In 1964 he produced and presented a BBC radio documentary on alcoholism hoping to make the treatment more available. A television programme on the same subject was made but never broadcast.

Riddell retired from the Ministry of Commerce in the 1960s due to ill health and dedicated his final years to writing. He had a weekly column in The Sunday News, and his plays were staged and broadcast on radio. Two books were published in 1972. Riddell had a reputation for being outspoken and controversial and he became a popular and regular pundit on Ulster Television and radio. He died in 1983 aged 78.

Extracts from ‘I Was An Alcoholic – The Story of A Cure’

by Patrick Riddell.

The specialist was not a tall man. He was not small but his broad shoulders and broad chest made him look shorter than he was. He had vitality. He had confidence. So much confidence, so much power … I murmured to myself, “This man is going to cure me!”

… The specialist spoke to my wife for twenty minutes. Then he turned to me. “Your wife tells me you really wish to be cured of alcoholism. Is this true?” “Yes” I answered.” He gazed keenly at me for a moment. Very keenly. “Good” – he said. He swung round to my wife again. “In that case” he said to her “he’ll do well.” I heard him tell her that the object of the treatment was to cleanse my brain tissue of alcoholic poison and thus set me free from the craving which had overmastered my will-power and compelled me to continue drinking alcohol. After the treatment, he said, everything would depend on my appreciation of the fact that I was never to drink alcohol again – never. He swung round to me- all his movements were rapid, dynamic – and spoke commandingly. I want you to give me two promises” he said. “The first promise is that you will not leave this Nursing Home until I give you permission. If you’re worrying about getting back to you job, you needn’t, you’ll be home again in a week.” I promised. “The second promise is that you will immediately drink every glass of whiskey the moment it is given to you either by the Day Sister or the Night Sister.” This amused me. The idea of my refusing to drink whiskey! I laughed. I noticed as I did so, a gleam in the specialist’s eye. “You promise?” “I promise.” “Very well, then.” Would you like a bath?” I said (yes).

… The Day Sister showed me to the bathroom, handed me a bath towel and soap and left me. I bathed quickly, slipped on my pyjamas, dressing gown and slippers and returned to the room. The specialist bowed to my wife and tapped my shoulder.

It was the signal. I took off my dressing gown and slippers and got into bed, bared my back and turned on my side. The injection was so deft I hardly noticed it. My wife stooped down and said goodbye ‘Mr Hyde’… I fell asleep.

Ten minutes after the injection the Day Sister wakened me and handed me a glass of whiskey. I drank the whiskey and was sick. “You’ve put something in it”, I said. She assured me she hadn’t. It was my own whiskey. All she had put into it was water. I had to believe her, although the whiskey certainly had tasted as if it had been doctored. Again I felt drowsy, again I fell asleep.

The treatment was not so bad, really, and the worst of it was over reasonably soon. What I would not wish to have to face again is the drinking of that horrible whiskey. Horrible? Yes. Every two hours the nurse gave me an injection. Ten minutes after every injection she gave me whiskey. On and on and on, by the clock, night and day, with compassionate mercilessness, they injected me with apomorphine and gave me whiskey. And the whiskey became more and more horrible, until I needed every ounce of my manhood I could call on to force myself to drink it. For the first time in my life I really smelt whiskey. For the first time in my life I really sense the evil in it.

On and on. Yes, they were merciless. I developed a terrible thirst for water, for common-or-garden water, the best drink – I came to realise it as I lay in that bed in that London nursing-home … But they refused to give me water, it would ‘break’ the treatment they said. They refused to give me a mouth-wash, they refused to allow me to brush my teeth, they refused to allow me to go to the lavatory, on the floor below, in case I should scoop up the water from the lavatory pan with my hands and drink it. They refused me a lemon or an orange. They allowed me – whiskey.

I slept and I dreamed and woke up with a cry and slept again and dreamed again. On and on and on. I lost touch with time. I didn’t know if it were day or night. I didn’t care. And, oh the sickness! After almost every glass of whiskey I vomited, either into the kidney basin on the table to my right or into the one on the table to my left. Always they were quickly taken away by a nurse other than the Day Sister – the Day Sister could not quit the room, as a patient undergoing the apomorphine treatment for alcoholism may never be left alone for even an instant – and were as quickly washed clean and brought back again from me to be sick in once more – and once more – and once more.

Not much longer to go. “Stick it boy, stick it,” the Day Sister’s voice, as she stroked my forehead to calm my sobbing, was gentle. I was perspiring, I was soaked in perspiration, but they would not sponge me. I might snatch the water filled sponge and put it in my mouth. I was hot, I was wretched with heat, but they would lift no blanket from me, they would not cool me. “Stick it, son, stick it.” The Night Sister’s voice was gruff, but there was kindness in it. “Stick it, Pat, stick it!” I heard myself whispering a quotation from St Mark ‘He that shall endure unto the end, shall be saved’ – and, despite the misery I was in, I smiled. I then experienced what many call hallucination. At this moment, this most deciding moment of my life, I felt that there were present in the room two men, dead long years before. Strange, immovable, impassive, they stood in a splash of shadow and looked at me. My body had in it something of their blood and bone and they looked to see what calibre I was of. The taller of them … – I recognised him from recollection of his portrait, which had hung in my father’s house throughout my childhood – was my great, great, grandfather, whose strength of nerve and purpose had brought him victoriously through seven Galway duels. The smaller was my mother’s father, one of the finest Ulster Scottish shipbuilders of his day.

… Another whiskey. Would they never stop bringing me that loathsome whiskey! I was weak. The Day Sister slipped her arm round my shoulders and helped me to sit up. “Come on – down the hatch!” No! No! But I had promised. And I meant to keep my promise. I meant to endure. I took the glass in shaking fingers, raised it to my lips, swallowed the whiskey, burst into perspiration and was sick. The Day Sister wiped my mouth with a soft dry towel. I dropped back on my pillow and fell asleep.

Again I had a seeming hallucination. I thought that my father and my mother and my wife came quietly through the doorway and the mist that swirled through the room and stood at the end of my bed and watched me.

… I cried out to them that I would win. But they did not seem to hear me. They smiled at me and turned away and vanished into the mist.

… Every two hours, an injection of apomorphine. Ten minutes after every injection, a glass of whiskey. Friday merged into Saturday. Saturday merged into Sunday. The effort to drink the whiskey became harder and harder. Not till my dying day shall I forget the ever increasing horror with which I saw the nurse holding out to me yet another glass of whiskey. I prayed. “Oh God give me strength to drink it!

… Nowadays I keep a decanter of whiskey in my house so that I may offer a drink to any friend that wants one. I can pour the whiskey into a glass and put soda into it and hand it to the guest without a qualm. I can sleep with an open glass of neat whiskey on a bedside table a few inches from my face, without thrusting it distastefully away and within wanting to thrust it away. I can spend hours in a public house or in a club surrounded by men drinking whiskey, and again feel no qualm. I am indifferent. But when I was drinking that whiskey in the Nursing home in London in October 1947, I felt I was forcing down my throat the leprous waters that wash the floors of Hell. And this was the drink I had thought attractive! This was the drink I had craved for, lied for, begged for – this was the drink that had ruined my career as a writer, that had all but ruined my marriage, that had seriously damaged my health and would assuredly cost me my life if I continued drinking it as I had been drinking it. My God!

Sunday afternoon. The peak moments of the treatment were approaching. And, for me, exhaustion was approaching. One concession had been made. My pyjamas, soaked with perspiration, had been changed. Twice. But the fresh pairs had not remained fresh for long, as I was now perspiring consistently and intensely. I was begging for water, imploring them to give me water, even if they only wet my lips with it. Steadfastly they refused and I heard myself sobbing again. The specialist arrived to supervise the last few hours of the treatment. I did not know he was in the room. He examined me, made certain tests. I still did not know he was in the room. For I was entering into the last and most terrible dream of all, the dream that heralded the end of the first and worst part of the treatment.

… Suddenly, the walls of the Nursing Home became clear to me. I saw the oil painting that hung over the fireplace. I saw the mirror that hung on the wall to my right. But as I look at these things they became covered with reptilian creatures that crawled rapidly up and down, up and down. Some of them were lizards and, as lizards have always horrified me, I screamed to the Day Sister to brush them away. She bent over me and told me that there were no lizards and that I was not to worry. If any lizards came into the room, she would deal with them. (I was in delirium tremens, the climax of the treatment). And with that she injected me again and then, ten minutes after, handed me a glass of something that was not whiskey. I swallowed it, she told me when the treatment was ended, without question and instantly fell into a restless sleep.

About an hour later – 5.45 p.m. on Sunday, 12th October, not much more than forty-eight hours from the time the treatment had commenced – I awoke. My eyes were blurred and I found difficulty in achieving focus. The mist that had hung about the room was still present, but not so thickly. Dimly, I saw the specialist and the Day Sister, sitting at the table in the middle of the room. Distantly, I heard the specialist speak to me. He asked me a question. When I realised what it was he was asking me, I could scarcely believe it. …. “Would you like a drink of water?” I gave a huge sobbing gasp of relief, for I knew that he would not allow me to drink water unless the worst of the treatment was over. I turned to the bedside table at my right. The kidney basin had been removed. In its place stood an enormous carafe of water, a tumbler and four bottles of fruit juice. Weak and shaking, I raised myself and reached for the tumbler. The Day Sister rose from her chair and poured a glass of water and supported me as I drank it – and continued to support me as I drank another – and another – and another.

An hour later they gave me some toast and a large cup of beef tea. I dislike beef tea, but this time it tasted like a drink from Paradise – in quality, second only to the water and the fruit juice I had drunk an hour before. (I had emptied the carafe and a whole bottle of lime juice.) They allowed me to brush my teeth and they helped me out of bed and gave me a sponge bath. They sat me in a chair, while they changed my bed linen, and they told me that I would have recovered strength sufficiently next morning to take a real bath. With this pregnant promise in my keeping, I got into bed again – the heaven of those freshly laundered sheets! And I asked the Day Sister to take down from my dictation the ‘heads’ of the terrible dream that had dominated the climax of the first part of the treatment.

This perturbed her. She stepped quickly across the room to me and read my pulse. I was not delirious, I assured her. I simply wanted to have a record of the main events of the dream before they faded from my mind. (The opportunism of writers!) She asked me why. Because I would someday write a book, I told her, about alcoholism and about the treatment which, I was now certain, would free me – and others like me.

… When I had finished dictating as much as I could remember, I lay back on my pillow and fell asleep. It was a good sleep. Dreamless.

When the Night Sister came on duty she found me awake and in such high spirits that she, too, suspected me and read my pulse. I chattered nineteen to the dozen as she did so and my excitability confirmed her belief that I needed to be put to sleep again. So she bundled me over on my side without ceremony, pulled down my pyjama trousers and game me an apomorphine injection as if she had been smacking a child. I laughed. Then I fell asleep.

Hours later I awoke and looked at my wrist watch. Mid-night. I felt extraordinarily wide awake and extraordinarily peaceful and happy. The muttering night-traffic of London did not disturb me or irritate me. It soothed me. My mind, I discovered – the realisation was sudden and surprising – was a different mind form the one I had brought with me when I entered the Nursing Home to take the treatment. But how was it different? How was I changed? I lay as still as I could, still as a soundboard, and waited. After a few moments, I heard Kinnaird’s voice, as clearly as if he had just entered the room, saying “Think straight, Pat!” For an instant I believed he had really entered the room and I raised myself and stared towards the door. But there was no one in the room save myself and the Night Sister. I glanced at her. She was seated in a chair near the fireplace, knitting. Obviously she had heard nothing. … My imagination was ‘having fun’. I lay back on the pillow once more and closed my eyes. Again Kinnaird’s voice sounded in my ear. “Think straight, Pat!” Again I looked towards the door, again I saw the room was occupied only by myself and the Night Sister, again I lay back on the pillow and closed my eyes and gave myself up to thought. And then I saw it.

Then I perceived the difference in my mind.

I was thinking straight!

Not only were the eyes of my head in focus, the eyes of my mind were in focus, too. I could look back across the years and see them in perspective. The true nature of my illness, its ramifications, its impact on my life and on my wife’s life, the damnable damage to my finances and to the career prospects of my children … The clarity of with which I saw it staggered me. And the picture dismayed me. … What had I done to deserve this dreadful illness which for twenty years had scourged me? … What had been the cause of it? Heredity? Had alcoholism been visited upon me as the sins of the fathers are visited? I made a resolve to study this disease, to find out all I could about it, to understand it, and then to write of it in such a way that others would understand it, too, and be saved from it as I had been saved. Yes, I knew I had been saved. There was to be two days later, a time of harrowing doubt, but, as I lay in that bed in that Nursing Home in the small hours of Monday, 13th October 1947, I knew that I was saved, that I had been freed forever from the malevolent fiend that had bedevilled my life and brought me so close to destruction.

The Night Sister was reading … I was very weak. The first part of the treatment, the first forty-eight hours, had taken a lot out of me. And, when one is weak, one is susceptible to self-pity. Heigho! Those ruined years. A tear fell on my cheek and before I realised it I was crying.

… The Night Sister stroked drew a chair to the side of my bed and sat down… She took the self-pity out of me as she would have taken a thorn out of my thumb. Then she gave me an apomorphine injection, punched my pillows to a comfortable condition straightened the eiderdown, tucked me in and bade me good night. In a matter of seconds I was asleep.

The specialist strode into my room at eleven o’clock on the morning of Tuesday 14th October – I had been in the Nursing Home about ninety three hours – and found me bathed, shaved, fully dressed and ready. I rose to my feet and was told to sit down again. I did so. The specialist sat in a chair that faced my own, looked piercingly at me and asked me how I felt. I said that I felt splendid and that I wanted to return to Belfast and begin rehabilitation. At once. He said that I could go back to Belfast when he allowed me. Not before. He had a few things to say to me first and there were a few things he wanted me to do first. Then – and only then – could I go back to Belfast. I bowed my head in assent. He had a way with him.

He pulled a white sheet of paper from his pocket, slapped it down on the table and drew on it a rough diagram of the human brain. Then he explained to me how alcohol had affected my brain and showed me with the help of his diagram the parts of my brain that had been affected. He made the whole thing clear to me. He explained the guilt complex I had suffered from when I was drinking. He explained the restlessness, the inability to concentrate, which alcoholism inflicts upon its victims. He explained the loss of moral fibre, the irritability, the defensiveness, the aggressiveness, the trembling hands, the morning sickness. He told me everything I had wished to know about my disease. He explained the treatment he had given me. Then he asked me where I had done most of my drinking while I lived in London. … I named (where I did my drinking). Very well he said – I was to spend two nights in my club before returning to Belfast and I was to make a tour of all the Chelsea pubs I had ever habituated. I was to drink orangeade in each pub and walk out of it, cocking a mental or actual snook at it as I did so. This command perturbed me. Was it wise that I should go again to these places? He did not answer me in words. He gave me an answer far more reassuring, far more valuable than any words he could have spoken. He put his head back and laughed. (I shall never forget that laugh: the confidence of it, the confidence it gave me was astonishing.) Then he rose from his chair, gave my ear a Napoleonic little tug, strode to the door in his customary dynamic manner and was gone before I could thank him. He had something of the rushing winds in his personality.

It was now half past twelve. … I was to have an early lunch as I was going out for an afternoon walk. With the Day Sister. She would be accompanying me because, while the specialist knew I would not relapse into whiskey drinking, I had not yet fully recovered from the treatment and might feel weak in the street. And if she were with me and I did have a weak turn in the street, she would tuck me under her arm and carry me back to the Nursing Home. (She was every inch of six feet, powerfully constructed, a handsome Amazon.)

… We went to Kew Gardens. … They delighted me. My restlessness, I had realised, had left me – another reassuring discovery. … 12 noon. Wednesday 15th October. The day of my release from the Nursing Home. The Day Sister had telephoned my club and reserved a room for me. I was to stay in the club for two days and two nights and cross back to Belfast on Friday 17th. I had asked the Day Sister to have lunch with me at the club and she had agreed. There remained one final talk with the specialist.

The door of my room was thrust strongly open and the specialist strode in. Again he sat on a chair opposite mine, again he looked keenly at me and asked me how I felt, again I assured him I felt well. He nodded. Then he asked me to write down on a sheet of paper four wishes, the four things I chiefly wished that life should give me. I was inwardly amused. What hokum was this? But as I greatly liked the specialist, I decided to humour him. I wrote down the wishes. There were: to be able to restore happiness to my wife; to be able to give my children a consistency stable background; to be able to hasten slowly; to be able to succeed as a writer. When I had finished, the specialist looked at the four wishes, accepted the first three and rejected the fourth. Attainment of the fourth was something he could not help me in, he said. It was a matter that only I could manage. Then he glanced at the table, picked up a newspaper, handed it to me and told me to read out loud from it. I was to keep my eyes on the printed page and concentrate on what I was reading. So far as he himself was concerned, I was to forget him.

I chose a column at random and began to read aloud. I tried to concentrate entirely on my reading and to keep my eyes from straying to the specialist, but occasionally and momentarily I failed. The glimpses I had of him showed me that he was walking up and down the room, his back turned to me, his hand clutching the sheet of paper on which I had written my four wishes. He was speaking in a strange and steady manner, but I could not hear what he was saying. Our voice intermingled, mine resonant, his subdued. Suddenly, he ceased speaking, strode over to me, knocked the newspaper out of my hand and said “That’s all!”

I looked at him. I was wondering what all this native-magic amounted to. He must have sensed my thoughts for he smiled a tight little smile and said to me – “You’ll soon know, you’ll soon know!” Then he hauled me to my feet, shook my hand grinned, wished me luck – and was gone.

The taxi stopped. I got out. Holding my helping hand, the Day Sister followed me on to the pavement. I paid the driver, took the Day Sister’s arm and led her up the steps to the main entrance of my club. I ushered her in through the swing doors and stood beside her in the hallway. And it happened.

I felt I wanted a drink!

I could sense myself turning pale. The terrible thought burst upon me that the treatment had failed. I was still an alcoholic, I would always be an alcoholic. No treatment on earth could save me. I was lost. My God! Lost, lost! I stood stock still. I heard myself groan. The Day Sister glanced quickly at me, said nothing, glanced away again and waited. I pulled myself together, took her to the special drawing room for women guests, found her a comfortable seat, murmured an apology and walked into the hallway again. I knew that there was only one place in the club where I could be sure of being alone. And I knew that I had to be alone, that I had to fight this fight by myself, that no friend, no ally, could help me. I walked across the hallway, down a corridor and into the lavatory. A few members were washing, brushing hair, straightening ties. I walked into one of the lavatory cubicles, closed the door, bolted it, sat down on the lavatory seat, learnt against the flush-pipe and closed my eyes.

Crisis. Did I have a physical desire for a drink or was it the associations of the club, in which I had done so much whiskey drinking, that made me think I wanted a drink?

Crisis? Yes. And I had to find the answer. If the answer were that I did physically want a drink, then I would cut my jugular vein and be done with it. (I had a pen knife in my pocket). If the answer were that the club associations were making me imagine things, then the treatment had succeeded and I was safe.

Make no mistake. When I say I would have cut my throat. I meant it. I would not have faced life, even the little that would be left of it, as an incurable alcoholic. Wife? Children? If I were to be an incurable alcoholic, they would be better without me.

I prayed. I asked God to let me learn the truth. I sat still, my eyes closed. I waited. I sat on the lavatory seat in such fear, in such wretchedness of spirit as even the crisis-struggle which had preceded my consenting to take the treatment could not have matched. Minutes passed. Five minutes passed. Ten minutes. Fifteen. Twenty. And still I sat there, still I waited.

I thought of the distress of my wife and my parents if they were to learn that I had taken my own life on the very day I had left the Nursing Home. The specialist and the two nursing sisters who had dealt with me would say – rightly – that I had reacted well to the treatment, that after it had ended I had been happy and in sound health. They would say that there was no explanation of my suicide, that there had seemed to be no reason for it. That I had been looking forward to re-joining my family, that I had been looking forward with an especially urgent eagerness to my return to Belfast in order to begin at once to rebuild my life and to make safe the lives of my wife and my children. I thought of the Day Sister, sitting in the special room for woman guests. Or was she? Surely by now she would have realised that something was wrong, that something she should know about was happening to me? She might be searching the club for me. A woman with her experience of alcoholics would have guessed the nature of the trouble I was in, would have risen at once from her chair to search for me and find me and take the glass of whiskey from my hand, however many club rules she might break in doing so. And if she had found me, found me with a glass of whiskey halfway to my lips, she would have taken me straight out of the club and back to the Nursing Home. And if she suspected that I had gone to earth in the lavatory she would have got one of the club servants to ferret me out. I knew her strength. I knew her determination to stand by her patients. I sat on my lavatory seat and listened for the knock of a club servant on the cubicle door. But no one knocked.

And then the answer came to me. (Which was exactly what the Day Sister wanted). The specialist had foreseen the ordeal and the Day Sister was under orders to let me ‘sweat’ it out myself.) It came clearly. I had no physical desire for a drink. It came suddenly and it came convincingly. I knew.

I looked at my watch. I had been in the lavatory cubicle for half an hour. I rose to my feet. Then I sat down again. Had a doubt stolen into me? Was that small sensation that had stirred within me a desire to go up to the bar and order a glass of whiskey? For another three minutes I waited. Waited. Waited. Waited.

It was all right. It was not a desire for a drink. The treatment had succeeded. I was cleansed forever of the craving. I was free.

Relief and happiness, such a relief and such happiness as I may never know again and hope I may never need to know again, flooded into me and through me until I could have shouted, shouted for joy, shouted, shouted, shouted.

Slowly I slipped from the lavatory seat until I was sitting on the tiled floor. And then, with my arms resting on that plastic lavatory sea in the National Liberal Club, Whitehall Place, London, SW1 and with my cheek resting against my arms and with my eyes closed, I whispered my thanks to God for my deliverance.